How reading let me down

You wouldn’t think reading could let you down. But as a young child it seemed to be at the root of most of my troubles.

Please don’t think I had a terrible childhood, or anything like that. In some ways, it could seem idyllic, growing up in a cottage in the woods of a country estate outside Henley on Thames. The cottage came with my father’s job as a groundsman. With only one neighbour in the gatehouse, around half a mile away, it wasn’t somewhere you could invite your friends from school.

On Sunday mornings, my father finished breakfast and settled back with his mug of tea and the newspaper. One morning, when I was about four years old, I spotted a photograph of the Beatles, boarding a plane for the USA on the front page.

Aware of my interest, he sat me on his knee and we looked at the newspaper together. Apart from the photograph of the Beatles, the headlines grabbed my interest. The different sizes of letters and words fascinated me, leading to a stream of questions.

As the Sundays passed, my father taught me to read, starting with the headlines and moving on to the words of the features. By the time I started primary school, I knew enough words to make steady progress through the book the teacher handed out in class.

This was my first mistake.

When he spotted me flicking through the pages, he came over, towering above me. His voice seemed to echo around the classroom. “Stop doing that and concentrate on the first page.”

“I’ve already read the first few pages,” I replied, unaware of my second mistake.

“What do you mean, you’ve read the first few pages?”

By now, everyone in class was staring at me. Their interest increased as I read the first couple of pages. However, the teacher wasn’t impressed. “Who taught you to read?”

Proudly, I said, “My dad lets me read the newspaper with him.”

His voice rose in volume after I said it was the Sunday Mirror. “You must stop this at once. I shall write your parents and instruct them to leave the teaching to those of us who are qualified to do it. Do you understand?”

I didn’t.

I had no idea what I’d done wrong. Why was I in trouble because I could read?

Angry at being singled out, and the unfairness of my teacher’s threat, I decided I didn’t need school. My father would teach me, each morning after breakfast.

I walked the mile and a half home, vowing never to return to school. My mother seemed horrified to see me, demanding to know why I’d come home. She wasn’t pleased to discover her four-year-old son had walked home unsupervised, crossing two main roads and walking down a long, lonely drive.

She was even more annoyed with the letter from the school. She started to criticise my father, who simply laughed, saying he would visit the school and sort these teachers out. He told me to take no notice but agreed to stop letting me read the newspapers with him.

Already despondent at having to return to school, this second blow hurt more. Until he came home one evening with a small box. He sat me down and passed me some books they’d let him have at the big house. While most of them were not much better than the ones at school, one caught my attention.

It was at least another year before I could read it without help, but it changed my life.

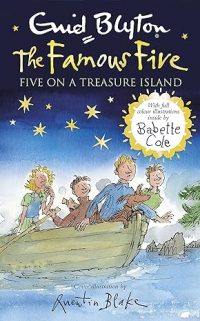

Five on a Treasure Island, by Enid Blyton, introduced me to the most influential series of books a young, enquiring mind could ask for. This was proper reading, where four ordinary children and their dog went on adventures I could only dream about. They solved mysteries, were often in danger, and had the kind of life I longed for.

More than this, they showed me a world I wanted to be part of. While I had to make do with what I had, my imagination created its own worlds, where I could have my own adventures.

Reading fuelled my imagination, allowing me to tell stories, turning my mundane life into adventures.

When my parents separated and my mother took us to Bradford-on-Avon, in Wiltshire, I joined a new school. Here was a fresh audience, who knew nothing about me. They seemed to enjoy my tales, though it didn’t take long before my popularity was challenged.

While my exaggerated tale of something that happened over the weekend bore a kernel of truth, one of the children listening walked up to me and called me a liar. Suddenly, my rapt audience perked up, sensing some action.

While I defended my story, it made no difference. The others had already followed their leader and begun to call me a liar. Within a minute, my challenger turned and walked away, his supporters following, still chanting ‘Liar’ at me.

The choice was simple.

Either I accepted I’d exaggerated a little and go with them, or stay put.

Whether it was a point of principle or an inbuilt stubborn streak, following meant admitting I was a liar. I hadn’t lied, so I turned and walked the other way.

This would turn out to be a regular occurrence in my life, though I had no idea at the time.

I would turn against any unfairness and injustice, whether targeted at me or those I cared about. The books I read helped to create this attitude, from the Famous Five to the Narnia novels of CS Lewis. Good would always overcome evil.

These beliefs were given a stern test the following year, when my father died from a heart attack, aged 37. I was eight years old. I had no comprehension of what his loss would mean to me, of how it would make me different and isolate me.

All I felt, apart from deep sadness, was the unfairness of it all.

And that’s what I started to write about.

You can find out more at my website, including details about my exclusive Readers Group. Or simply enter your details below.